A Representational Style of Art in Picture Books Can Be Described as

From cavern paintings to Maurice Sendak, a look at the masters of the form

Back in the fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci made the following remark near visual storytelling:

"And you who wish to represent by words the course of human being and all the aspects of his membrification, relinquish that thought. For the more minutely you describe the more y'all will confine the mind of the reader, and the more you will keep him from the noesis of the affair described. And and then it is necessary to draw and to describe."

From very early on on, we both intuit and learn the language of pictorial representation, and most modern adults, the picturebook was our first dictionary of this visual vocabulary. Nonetheless the picturebook -- defined by its narrative framework of sequential imagery and minimalist text to convey significant or tell a story, and different from the illustrated book in which pictures play a secondary narrative part, enhancing and decorating the narrative -- is a surprisingly nascent medium.

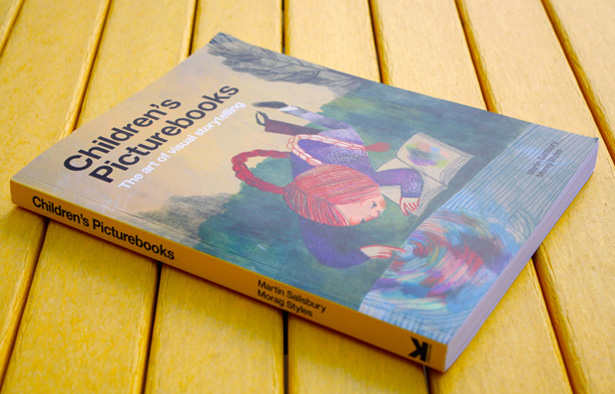

In Children's Picturebooks: The Art of Visual Storytelling, illustrator Martin Salisbury and children'southward literature scholar Morag Styles trace the fascinating evolution of the picturebook as a storytelling medium and a cultural agent, and peer into the time to come to encounter where the medium might be going side by side, with case studies of seminal works, a survey of artistic techniques, and peeks inside the sketchbooks and artistic process of prominent illustrators calculation dimension to this thoughtful and visually engrossing journeying.

Though pictorial storytelling dates back to the earliest cave wall paintings, the true picturebook harks back to a mere 130 years ago, when artist and illustrator Randolph Caldecott (1846-1886) first began to drag the paradigm into a storytelling vehicle rather than mere decoration for text. Maurice Sendak, widely regarded as the greatest author of visual literature (though he refuses to identify as a "children'due south author"), one time wrote of Caldecott's "rhythmic syncopation" and its legacy:

"Caldecott's work heralds the beginning of the mod picture book. He devised an ingenious juxtaposition of picture and word, a counter pint that never happened before. Words are left out -- but the film says information technology. Pictures are left out -- but the words say it. In short, it is the invention of the picture book."

Even early, tensions betwixt the artistic vision and marketability of picturebooks captured the same friction betwixt artist-storyteller and publisher that continues to plague children's -- if not all -- publishing. Walter Crane (1845-1915), another Victorian-era picturebook innovator, famously grumbled nigh printer-publisher Edmund Evans' approach to publishing:

"...but it was not without protest from the publishers who idea the raw, coarse colours and vulgar designs commonly current appealed to a larger public, and therefore paid improve..."

(Evans, per Crane's remark, seemed to have taken on the role of a "circulation manager" of books, and with that came the same perception of compromised editorial integrity we've previously seen in the context of newspapers.)

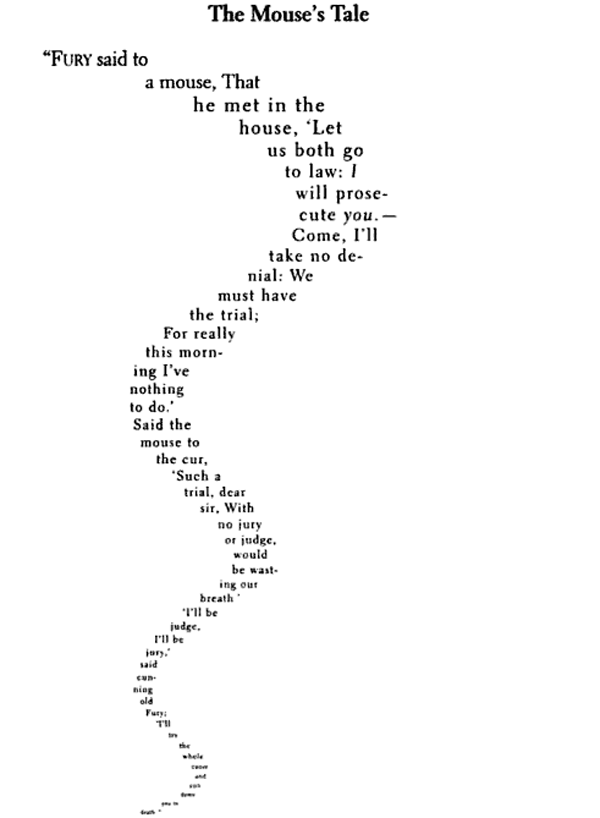

Lewis Carroll's The Mouse'southward Tale is an early instance of text taking the visual form of that which it describes or alludes to.

Only the picturebook didn't fully blossom until the belatedly nineteenth and early twentieth century, when new developments in printing engineering science, changing attitudes towards childhood, and a new class of infrequent artists catapulted it into a gilt historic period. The first three decades of the twentieth century germinated such timeless classics as Curious George and the Babar stories. But as war consumed Europe, resource dwindled and the newspaper shortages of the post-war era placed new demands for keeping publishing costs low. However despite, or possibly because of, the thrift of the time, there was a profound longing for color as escapism, which reined in the neo-romantic movement.

Then, in the 1950s, a peculiar cultural shift began to take identify -- the line between artist and writer started to blur, and a crop of famous graphic designers ready out to write and illustrate picturebooks as a way of exploring visual thinking. (Just this week, ane of the virtually celebrated such gems, the but children'southward volume by the great Saul Bass, resurfaced to anybody's delight.) Amidst the highlights of this new borderland was a series of children'south picturebooks by legendary graphic designer -- and, paradoxically, notorious curmudgeon -- Paul Rand.

He and his so-wife, Ann, produced Sparkle and Spin (1957), Picayune i (1962), and Listen! Listen! (1970), all an exercise in demonstrating "a playful but sophisticated agreement of the relationship between words and pictures, shapes, sounds, and thoughts." (It was in the same menses that Italian novelist and philosopher Umberto Eco introduced immature readers to semiotics, the written report of signs and symbols.)

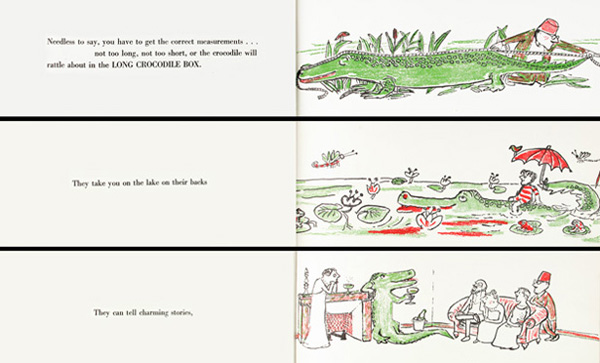

André François's Crocodile Tears (Universe Books NY, 1956) uses an extreme landscape format to reflect and emphasize the subject field matter. Information technology was François's first picturebook every bit writer-artist.

In Um Dia Na Praia, flat color without line is used with careful attending to the placement of every element in order to develop a wordless text. The very uncomplicated shapes need to carry the entire weight of a subtle pictorial narrative.

Just many of these pioneering picturebook storytellers, just like Sendak does to this solar day, had an aversion to identifying as "children's book" authors. Salisbury and Styles write:

"Of course, many of the best picturebook artists would not depict themselves exclusively equally such. André François was born in Hungary, in an area that became part of Romania after World War I. But it was as a French citizen that he spent his working life as a graphic artist, spanning visual satire, advertisement and poster design, theater set design, sculpture, and volume analogy. François'southward work exhibited a childlike awkwardness that belied a highly sophisticated, biting eye."

(Audio familiar?)

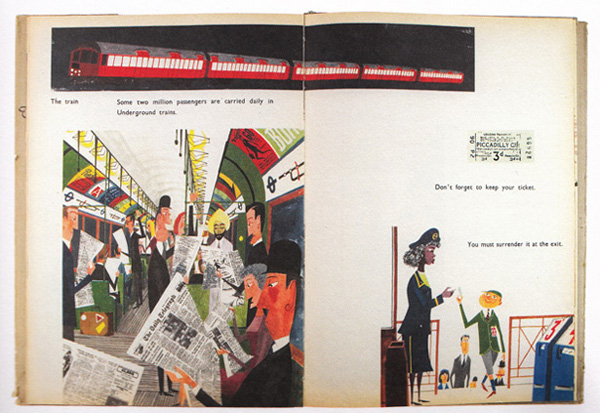

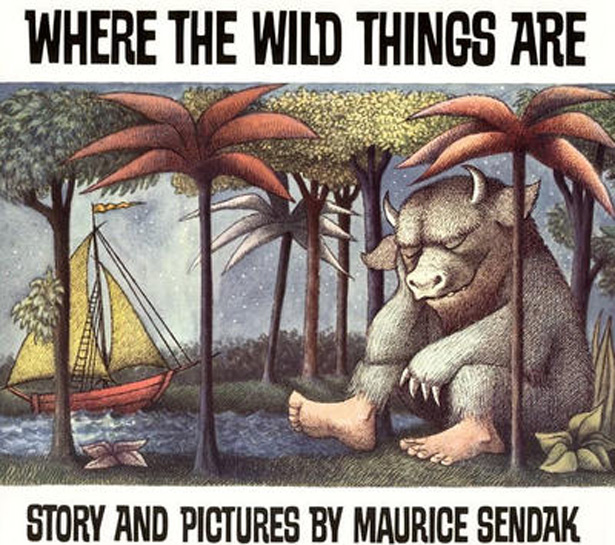

In the 1960s, as a generation of British artists emerged from art school, picturebooks entered a new era of vibrant pigment and color, with many artists combining volume illustration and painting to make a living. (Including, as we've seen, Andy Warhol.) It was in that era that some of the most influential picturebooks were built-in, including Maurice Sendak'south most beloved work and Miroslav Šašek'due south timeless This Is... series.

Miroslav Sasek's 'This is...' series introduces children to countries and cities around the globe. What distinguished them from many such books was the artist's eye for the anecdotal detail of unlike cultures. This is London was published past MacMillan in 1959.

(Don't miss Šašek'south lesser-known 1961 gem, Stone Is Not Cold, in which he brings to life famous sculptures from London, Rome and the Vatican city in irreverent vignettes from everyday life.)

"Maurice Sendak may exist the greatest illustrator for children of all time and was certainly 1 of the earliest to make an impact on educators and scholars, equally well as on children, parents, and the creative community. Where The Wild Things Are (Harper & Row, 1963) was no Sendak'south starting time picturebook, merely information technology was the kickoff one to make a huge impression on children and adults alike. Interestingly, it caused a furore when it was published, with many critics anxious that information technology would be too terrifying for children."

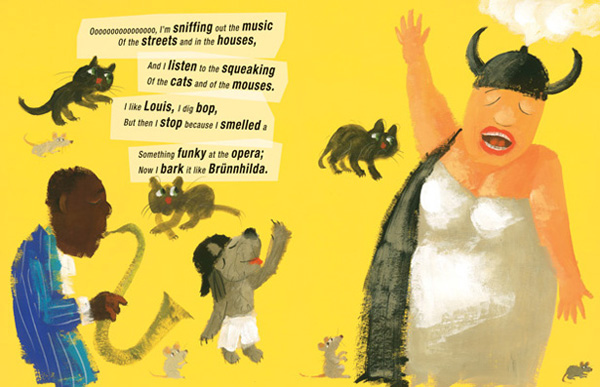

Vladimir Radunksy's swirling vortex of type and paradigm perfectly complements Chris Raschka'due south rap text in Hip Hop Domestic dog.

(You might recall Vladimir Radunsky, above, from his fantastic illustrations for Mark Twain's Advice for Little Girls.)

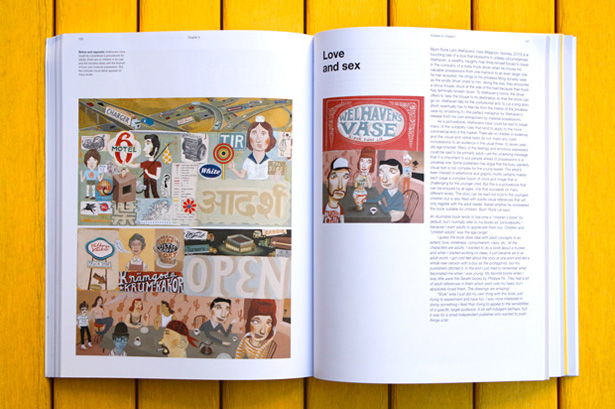

But the book's about fascinating feat is its discussion of the socially constructed and increasingly fluid criteria for what is suitable for children, with complex themes like violence, sexual practice, death and grief, and human rights violations turning picturebooks into a powerful crossover storytelling medium for all ages. Even some of the virtually beloved storytelling of all time, like The Brothers Grimm fairy tales and Arabian Nights, was aimed at children but often featured dark, even savage, themes, and picturebooks have a documented history of radical politics.

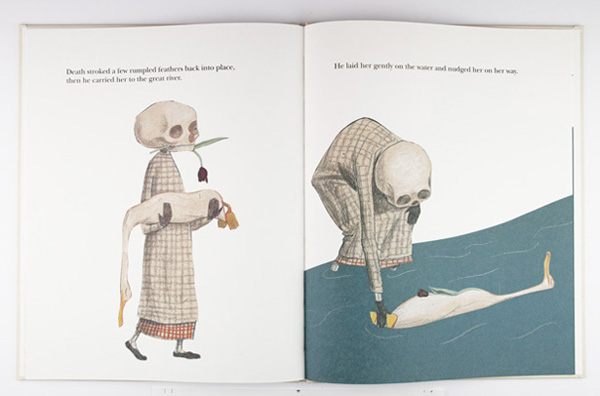

The bleak, uncompromising visual and exact text of Wolf Erlbruch's Duck, Expiry and the Tulip.

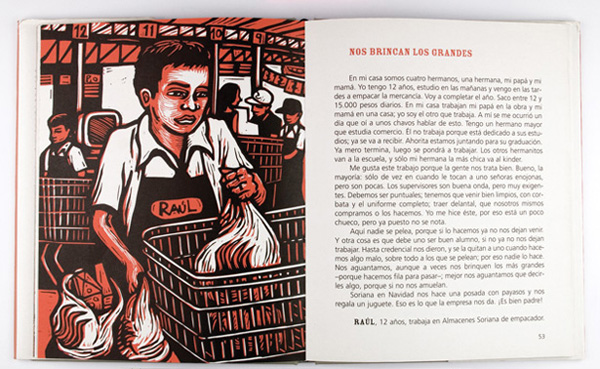

No Hay Tiempo Para Jugar / No Time to Play (text Sandra Arenal, illustrations Mariana Chiesa; Media Vaca, 2004). Produced in typical Media Vaca hardback format, the volume gives vocalism to the child laborers of Mexico in words and pictures.

Paradoxically -- and disappointingly to those of us who celebrate the cantankerous-pollination of genres, ideas, and narratives -- traditional booksellers and the marketing departments of major publishers have remained oddly stringent about how picturebooks are labeled and sold, confining them strictly to children's literature. (For an example of merely how short that sells them, see Blexbolex's fantastic, layered, remarkably thoughtful People, as delightful to kids as information technology is thought-provoking to adults -- yet it remains shelved in the children's section at the Large Corporate Bookstore.)

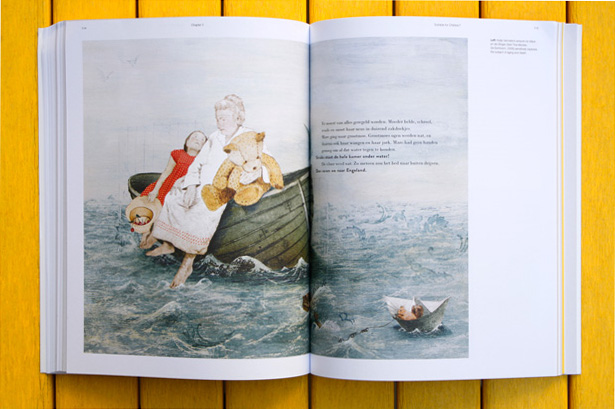

Color woodcuts by Isabelle Vandenabeele from Geert De Kockere'due south Vorspel Van Eeen Gebroken Liefde (De Eeenhoom, 2007)

The CJ Picture Book Festival in South korea seems to become this crossover evolution, stating in its manifesto:

"Motion picture books, in the present era, enjoy a status as a civilization form to be enjoyed by people of all ages. It is a precious and versatile art that has already left the confines of paper backside, shattering the boundaries of its own genre and fusing with various other forms of fine art and imagery."

The unique developmental capacities of children, Salisbury and Styles signal out, likewise shape the stylistic suitability of visual texts, presenting their ain ready of paradoxes and challenges:

"Many publishers and commentators express views about the suitability or otherwise of artworks for children, yet in that location is no definitive research that tin can tell u.s. what kind of imagery is almost appealing or communicative to the immature center. The perceived wisdom is that bright, master colors are most constructive for the very young. The difficulty is that children of traditional picturebook age tend not to have the language skills to limited in words what they are receiving from an epitome. They tin also be suggestible and prone to saying what they imagine adults want to hear. And so, even with the all-time designed research projects, the world that children are experiencing will inevitably remain something of a mystery to the states."

In her Chain of Happiness illustration, Marta Altes screen-prints with three colors.

Then where is this ever-evolving medium headed? Salisbury and Styles cite gaming programmer turned children's volume illustrator Jon Skuse, who articulates both the tragedy and infinite potential of today'south children'southward ebooks beautifully:

"The eBook isn't about winning or losing. It's near an 'exploration,' and experience, rather like a pop-up book. What many publishers are doing wrong at the moment is only copying printed picturebooks on to this format, which does both media a disservice. It's just like looking at a PDF. Children volition simply movie through. A printed picturebook is a particular kind of physical experience that tin can be savored and revisited. The eBook needs to exploit its ain particular characteristics and strengths to evolve as similarly special but distinct experience."

The authors conclude with a metaphor for the future of picturebooks borrowed from Lane Smith's fantastic It's a Book:

Peradventure the last discussion (or, rather, the last word and picture) should go to that modern principal of the idiom, Lane Smith. In his new picturebook, It's a Book (Roaring Book Press, 2010), Smith's ape tries to explicate to Jackass that the thing he is holding is called a book. Among the stream of questions asked by Jackass are: 'HOw exercise you curl downwards?', 'Does it need a password?', 'Can you tweet?' and 'Can y'all make the characters fight?'. When Jackass somewhen gets the hang of this strange object, ape is forced to enquire 'Are you going to give my book back?'. 'No,' replies Jackass."

As fascinating and rich every bit Children's Picturebooks is, it suffers one conspicuous contradiction -- with its concern with the format and future of the book, and its multitude of references to other books and historical materials, a kind of baked-in framework for truly networked noesis, it would accept, and should have, easily lent itself to the digital medium, where each of the dozens of books mentioned would exist linked and explorable in rich media. Still, it remains a rigorously researched and compellingly curated survey of a tremendously of import storytelling medium, one that equips young minds with a fundamental understanding non only of the earth only also of its visual language.

This post appears courtesy of Brain Pickings, an Atlantic partner site.

Paradigm credits: Laurence King Publishers

We want to hear what you lot think about this commodity. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Maria Popova is the editor of Brain Pickings. She writes for Wired UK and GOOD, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/02/a-brief-history-of-childrens-picture-books-and-the-art-of-visual-storytelling/253570/

0 Response to "A Representational Style of Art in Picture Books Can Be Described as"

Post a Comment